Over the past two months I have been deeply entrenched in the whirl of the COVID-19 pandemic, awoken each day to reports of the vast numbers of elderly Italian people whose lives have been taken by this powerful virus–merciful in sparing our children and young adults. But with that, I have been deeply saddened by the loss of our elders in a Western culture that has long forgotten to see, respect and give close ear to the aged.

I’m here to reflect upon and speak to my own decades-long love story with Italy’s elders.

With hundreds of people dying each day at a rate that is overloading Italy’s public health system beyond words, most of our passing elders are either being met with delays, buried or cremated without ceremony or the presence of family to grieve and honor their lives. Hospital workers are scrambling. Funeral companies are stretched. There are no last goodbyes, no gatherings in prayer, no meals. No healing moments.

Last week I traveled six hours South to a tiny mountain village near the sea. I drove down with a dear friend who owns a delightful house wedged in between the crevices and abandoned houses of this precious place called Camerota; another one of Italy’s many crumbling, declined, forgotten villages. Later that evening, Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte announced a nationwide rigid lockdown. My heart sank. There I was. In the South. Not home.

But in some ways, home.

The next day I was greeted and chauffeured around by a dashing, debonair local elder. Born and raised in Camerota, a fiercely proud retired tour guide, Arnaldo is one of the last, original Cicerone (guide)–an old job or title that is hardly used today. This very important title Cicerone comes from Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 B.C.) who was renowned in Rome as a statesman, lawyer, and writer whose eloquence and learning influenced the use of his Italian name to refer to sightseeing guides known for their talkativeness and eloquence and later the name or title given to those who served as mentors or guides.

Arnaldo is the truest of gentleman. His eyes lit up and his spirit came alive as he spoke about the history of his beloved village. Now in his late 70s, Arnaldo could not help to mention almost immediately how he feared the arrival of COVID-19 in the South due to the unpreparedness of the local infrastructure and hospitals. I could feel his worry and wonder about what this would mean for his community, his people.

He and I spent days roaming the streets of Camerota, visiting the churches and museums, pouring over maps of the coastline and deciding on the best possible walks in this gorgeous corner of the world, just south of Salerno, along what is referred to as the Cilento Coast. He arrived every morning sharply dressed and excited to meet the day. Sometimes, after dinner, he’d passed by to drop off a copy of an article he had written or an excerpt from one of the many books he had written or contributed to over the years. In just a matter of days Arnaldo came alive with story after story. He felt his very purpose rekindled. This was beautiful to both witness and to participate in.

Yet my experience with Arnaldo was not necessarily unique or unusual. In the (almost) three decades I have been working and living in Italy I have witnessed and experienced an extraordinary passion, drive, and excitement around the collective natural and creative worlds. Mostly shared by older Italians. Growing up in an Italian emigrant family back on America’s eastern shores, this somehow always delivers comfort, touching intensely familiar chords.

Caroline McHugh, Scottish author of Never Not A Lovely Moon writes and speaks about how great we are at being ourselves when we are kids and then again as elders. Imagine life as an hourglass where the squeezed bit in the middle represents the most challenging, difficult chapters. Filled with social perceptions and ego. It’s now clear to me why I have met so many elderly people in all my years as an expatriate in Italy. Most often there is no judgement, preconceptions, feelings of superiority or inferiority. What little (or lot) they have to share has always been generously given away; I’ve been invited in and encouraged to sit, chat, watch, learn, and most importantly, listen. Older Italians have mastered McHugh’s “art of being themselves.” I could fill a memoir about many of these profound experiences that have elevated me to absolute joy, time and again.

My life work has been–and continues to be–precisely this: sharing these age-old traditions; the Italian people, their habits and rituals in daily life, the extreme importance of good food, respect for craftsmanship, beauty, forgotten methods and in some cases, ancient ways of living life––that somehow still work in the mixed modern life of the older Italian.

They remember.

For the past 28 years I have created a life for myself that focuses on taking guests around Italy to experience these precious people. I’ve been more than welcomed and invited into homes while doing research (and then later revisiting with my American guests) to experience and learn a simple (or not so simple) craft or life work. To walk alongside them through their green, thriving vegetable gardens, revel in and embrace their most self-taught knowledge about anything and everything from weaving textiles or baskets, churning clay for terracotta, cooking mosto for aceto balsamico, making pecorino or parmesan cheese; pruning their treasured olive trees, foraging herbs, asparagus or mushrooms, working the vines, hunting game or truffles. You name it, they do it.

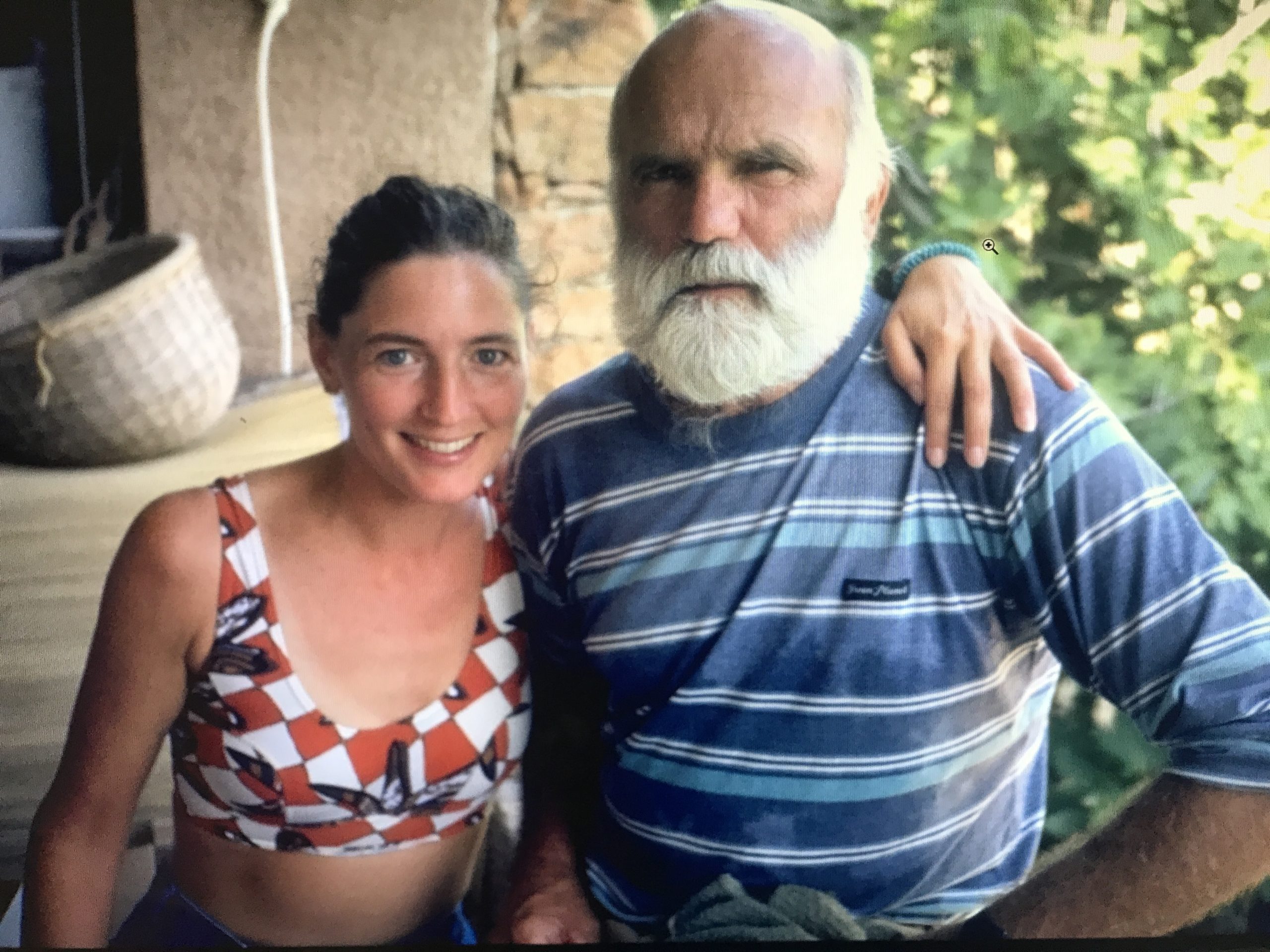

Photo: Carol and Guiseppe, Corsica (circa 1995)

These are the pastimes and the livelihood of Italy’s elders. Most of them spend their days in the outdoors, climbing trees or up and over steeply, terraced land–stretching the limits of their aging but incredibly strong bodies. Beyond belief. With great pride. Doing what they love but also, what comes natural to just being. But, who will carry this forward? Who will care as much? What will happen to all this wisdom and heritage? Will they merely be forgotten or only remembered as dusty post-card images of time and place?

A few years ago while leading a bicycle tour in Tuscany’s Val d’Orcia, my group and I landed in the small village of Pienza. That evening we stumbled upon a festival that included locals waltz dancing in the main piazza. My guests were beyond delighted and for some, this was the most memorable event of the week. All of Pienza’s elders were there, dancing their ballo liscio–beautiful and elegant beyond belief. Amazing dancers came out of the woodwork. One older man was relentless about inviting me to dance and as I tripped over my feet, stumbling and laughing–he led me through several challenging waltzes. Later, I discovered that Armando, a passionate cyclist himself, ran a historical bike repair shop in town. Coincidence and destiny collide, once again.

Photo: Armando and Carol, Pienza, Tuscany

Earlier that day, we had been fortunate enough to catch the tail end of the Fiera del Formaggio (Cheese Festival). The highlight of this festival was a game called Cacio al Fuso (literally: “cheese to the spindle”) a sort of bocce ball game played with pecorino cheese rounds. That’s right folks, it’s a local game that began decades ago in the backyard of a nearby farmhouse. Pienza’s six districts (contrade) compete for the prize (il palio). Ninety-year-old Armando is the oldest player. All participants get three rolls to get the cheese closest to it’s target. The top player from each contrada competes in a final challenge to determine the winner who then claims glory by gaining points for their contrada. I found out later that this glorious festival traditionally finishes with an evening of waltz dancing in the main piazza, which we gleefully attended. And, so of course, it was there I danced the night away with beautiful Armando.

Photo by Frank Yantorno

But these are stories from an endless pool. Arnaldo and Armando are just two bright stars in a vast galaxy of untethered souls. There are hundreds of these memories, stories etched into the corners of my mind. Three decades of awestruck moments, warm exchanges, invites into humble homes, barns, olive groves, studios, kitchens, vineyards, and makeshift workspaces. So much laughter and love and deep, visceral pride. These people exemplify Mahatma Gandhi’s words: “my life is my message.”

Photo: Chef Giovanna & Carol, Bologna, Emilia Romagna

It’s an odd sensation now to pass all the empty piazzas, empty bocci ball courts, closed bars and billiard rooms. It’s strange to no longer hear the banter of older men gathered around the stadium; the clusters of women in front of the churches, at markets and in butcher shops.

The elderly people of my beloved Italy stole my heart from the very beginning and well, this love story is not over, yet.

Carol Sicbaldi